Have you picked your first blackberries yet? Down here in the south-east of England, where we’re enjoying a really super summer (apologies to all those in the rest of Britain who’ve been washed out (again)), blackberries started ripening around three weeks ago.

Have you picked your first blackberries yet? Down here in the south-east of England, where we’re enjoying a really super summer (apologies to all those in the rest of Britain who’ve been washed out (again)), blackberries started ripening around three weeks ago.

And, thanks to a garden experiment I began a couple of years ago, we're enjoying the bounty. For years, we’ve hacked back all brambles without question. Then, hacking yet again at a particularly powerful shoot that resurrected itself, no matter how often I cut it down, I deliberated this (literally) fruitless activity. Why not give it its head?

Most brambles, especially in shade, are weedy, spindly growths that, in my experience, will never produce decent fruit. But this was a powerful stem in full sunshine and a sheltered position. So, in the face of fierce family opposition I let it grow.

Last year it bore well but this year we have a fruit harvest writ large. Pints of blackberries have ripened already, with plenty more to come. Part of the bush is even still in flower. (It’s a funny year.) And the blackberries themselves are enormous – bigger than anything I’ve picked in the wild, although it is itself a wild bush. My only problem is how to prune it.

Often advice is to train blackberry stems according to their age: in one direction one year, the opposite direction the next year. Fruit is produced on two-year-old canes, which is why you should keep the current year’s growth separate. Fruited canes are pruned out from the base after harvesting, and the year’s new fruits are trained in their place.

Often advice is to train blackberry stems according to their age: in one direction one year, the opposite direction the next year. Fruit is produced on two-year-old canes, which is why you should keep the current year’s growth separate. Fruited canes are pruned out from the base after harvesting, and the year’s new fruits are trained in their place.

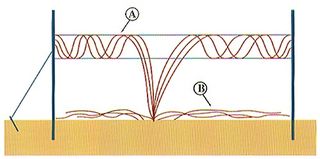

As usual, one of the excellent US Extension Colleges - this time belonging to Oregon State University - gives full instructions on dealing with blackberries. The diagram above shows the current year's growth (primocanes) laid out on the ground, with the fruiting canes (floricanes) having been tied in the previous autumn. They also give instructions on light pruning of the primocanes.

The RHS website does it differently, suggesting bundling new canes together along upper wires, then retraining them on lower wires, once the fruited canes have been removed from them (sounds harder work!).

But my bush, shaped in a hummock, has nothing so tidy about it. The RHS website warns: “If you don’t have somewhere to train these berries, they will quickly grow out of control and be harder to prune and less productive.”

I admit it’s only just under control. I foresee a lot a scratched flesh this autumn as I try to sort out the different canes. Still the council just hacks wild bushes back year after year and they continue to fruit, so I guess we don’t have to be too prissy about it.

So, if you have a bramble that just won’t go away, why not give it a chance and take advantage of Nature's bounty? And if you've given this a go, click on comment below and let us know how it's gone.

August seems a little early to mention bare-root fruit trees, as these don't go in until November at the very earliest, but here's something that you need to know about now if you're interested. If you think you might be adding a fruit tree to your garden this winter, but aren't sure what to order, then this opportunity from Orange Pippin Fruit Trees (NB 2014: offer now discontinued) might help your decision.

Recent Comments